Building the Future

The COOP group of retailers in Italy is the largest and fastest growing co-op sector in Europe. For U.S. food co-ops, how COOP, a confederation of consumer co-ops, became the market leader in Italy is well worth understanding. Four factors made a difference in the development of the COOP group:

Change: After World War II, the thousands of cooperatives had to either change or die.

Challenge: The postwar economy created a very different world of retail and consumer demand.

Capital: To grow and compete, co-ops

needed funds, and two laws created financing innovations.

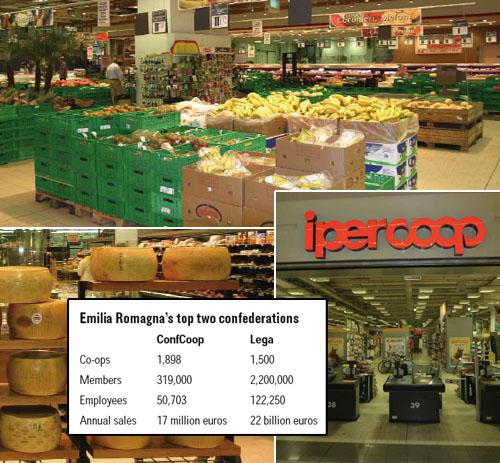

Clusters: Clustering cooperative development increases solidarity and reciprocity, and the best example of the synergy of clustering has made cooperatives about one-third of the economy in the region of Emilia Romagna.

To understand the cooperative sector in Italy, a little background is needed. There are three confederations of cooperatives, which began as being politically distinct and competitive with each other. Over the past two decades, there has been a lessening of distinctions and an increase in collaboration. Certain generalizations remain, however:

- The Lega (League of Cooperatives) is associated with the Left parties.

- The ConfCoop (Confederation of Cooperatives) is associated with the Catholic center Right parties.

- AGCI, the Association of Cooperatives, quite small compared to the other two, is associated with the Republican parties.

Most cooperatives are linked to the national organization, at the provincial level, and at the sector level such as consumer co-ops or housing co-ops. (For more background, see “Italy’s Emilia Romagna” in CG #109, Nov.–Dec. 2003.)

This article focuses on the growth of the COOP group associated with the Lega. There are 1,276 COOP-branded stores with $15 billion in sales, some 51,800 employees, and 5.9 million members. The COOP group does 17.7 percent of the grocery volume of Italy, followed by Carrefour at 9.7 percent. Carrefour is a publicly held, French-based multinational and second only to WalMart in world retail sales.

Change and challenge in the postwar era

From the time Mussolini came to power in 1922 and through the end of World War II, cooperatives were controlled by the Fascist government. During the Second World War, many cooperators associated with the Lega became members of the partisan (resistance) movement. Numerous cooperators were either imprisoned or executed by the Fascists and/or the Nazis. The Italian Communist Party (PCI) took the lead in organizing the wartime partisan movement, which fought the strongest in the Red Belt regions of Emilia Romagna and Tuscany. Following the war, the PCI was democratically elected to govern the Emilia Romagna region and many communities within the Red Belt.

At the end of the war, the Lega was governed by a leadership coming mainly from the PCI, other Left parties, and the partisan movement. In that era, the PCI’s highest objectives were to extend trade unionism and to organize cooperatives to serve small business owners. In the postwar era the Lega focused on developing CONAD, a national secondary cooperative of independent grocery stores, rather than developing consumer cooperatives.

By the 1970s, the Italian consumer cooperatives were fast losing market share. Ivano Barberini, now president of the ICA, remembers, “There were too many single-store societies, minimal coordination at the regional or national level, and few supermarkets or signs of modernization. Four of the top 10 co-ops in the Lega were failing.” The 1970s could easily have been the decade in which much of the consumer co-op sector would die.

Fortunately, enough Lega consumer co-op leaders realized a new vision had to be forged, and plans had to become actions. The 1970s were an era of great struggle and great change. Many small societies died; 3,000 small individual societies merged into 200 regional co-ops; and 7,000 small co-op shops were closed. Costs dropped, efficiency increased, and the co-ops moved back into profitability.

The next battle was whether cooperatives should operate hypermarkets. Chains with hypermarkets were gaining huge market share, while others were not only losing market share but purchasing power. The French chain Carrefour was the leader in transforming itself from a national to multinational player with no boundaries to its retail reach. On the other hand, most Italian cooperatives were still unwilling to unite their resources to even be a national player.

Some consumer cooperatives in Emilia Romagna determined that hypermarkets had to be a part of their retail mix. None of the other co-ops wanted to guarantee such an investment. In 1988 the co-ops of Emilia Romagna opened up five hypermarkets which, without allies, were left to sink or swim. Fortunately, the plan worked, and sales and profitability increased dramatically. Once the hypermarket model found acceptance, other co-op societies followed. By the end of 2005 there will be 78 co-op hypermarkets throughout Italy.

Co-op Italia

With the regional societies generating increased volume, the co-ops began to look at revitalizing Co-op Italia, a national buying agency for the Lega’s consumer co-ops. Previously, most local societies purchased directly and had limited use for Co-op Italia. Co-op Italia was reorganized to craft national purchasing contracts, to source private label products, and to warehouse and distribute nationally. The COOP label is now 30 percent of all private label volume in Italy and applies to 1,000 manufactured and 1,500 produce items. In co-op shops, the COOP label creates an average of 26 percent savings for the consumer over similar brands.

Co-op Italia has a very successful sophisticated private label program. The COOP brand is separated into one of seven distinct subbrands, such as fair trade, organics, and health. The consumer trust in COOP label is very high due to the quality and value. Sales overall have strongly increased since introduction of the subbrands.

Some facts about Co-op Italia:

- There are now 175 consumer co-ops affiliated with Co-op Italia.

- Co-op Italia is now open to any consumer co-op, no matter the affiliation.

- The nine largest affiliated consumer co-ops do 90 percent of Co-op Italia’s business.

COOP is the Italian leader in the sale of organic and locally grown products and the promotion of small farmers.

During 2004, co-ops affiliated with Co-op Italia gained 525,000 new members, a 14 percent increase in national membership.

COOP members make up 70 percent of all purchases from COOP stores.

Within the nine largest co-ops in Co-op Italia, 1 million members (19 percent of total membership) are also lenders to the co-ops; members can invest in COOP shares at the cash register and obtain a higher interest rate than in a bank.

Capital

Under Italian cooperative law, there are two mechanisms that play a major part in financing cooperative development both at the local co-op and the national level. Both laws would certainly boost cooperative growth in the USA:

Law #1 3 percent of the net profits of

all cooperatives must fund cooperative development.

Law #2 No tax is levied on a percent of the profits retained within the cooperative when allocated to indivisible reserves.

Law #1: Three percent of profits fund co-op development.

Since 1992, every cooperative (not just consumer co-op) corporation in Italy has had the responsibility of transferring 3 percent of its net profits to a national cooperative development fund.

Three different funds were set up to support co-ops affiliated with either;

1) The Lega (Left of center),

2) ConfCoop (Catholic center Right), or

3) ACGI (Republican parties)

The Lega’s Coopfond (Fund for the Promotion of Cooperatives) is the largest of the three and is used here as an example of all three funds. By the end of 2004, Coopfond had a cumulative balance of over $300 million. Coopfond is growing by about $25 million a year through contributions from profitable cooperatives. The number of contributing profitable cooperatives has ranged from 3,760 in 1993 to 3,975 in 1997.

Coopfond has the flexibility to make loans at below-market rates, with favorable conditions or lengthier terms. Coopfond is a great resource for new cooperatives meeting the needs of new markets since those cooperatives usually lack access to capital in the early stages of development.

The 3 percent of net profits is sent to the national Coopfond, which determines where the funds will be invested in cooperative development.

Presently, about 40 percent ($104 million) of the cumulative income of Coopfond comes from the profits of consumer cooperatives, whereas consumer cooperatives have received only 20 percent ($36 million) of the loans. Coopfond’s present objectives emphasize investing in food production by farm cooperatives to strengthen farmers and rural Italy, and in service and tourism cooperatives to strengthen social service, agri-tourism, and rural services.

A second noteworthy aspect of the national development fund is that 76 percent of the income to Coopfond comes from Northern Italy, 21 percent from Central Italy and only 3 percent from Southern Italy. However, 27 percent of the funds go to the South, 21 percent to the Center and only 52 percent go back to the North. The Lega also has a set of long-term objectives focused on building a cooperative sector in the South, which remains by far Italy’s poorest area and with the fewest co-ops.

An additional legal requirement that grows the Coopfond is related to the dissolution of a cooperative, since all remaining assets must be transferred to Coopfond. The Lega outlines this philosophy as follows;

“In the event of an enterprise being liquidated, the company assets must be put into the cooperative promotional fund (Coopfond) that is used to promote the creation and development of other cooperatives. Whereas the shareholders of an ordinary company are its actual owners, the members of a cooperative simply manage assets with a solid territorial identity that will eventually be passed on to future generations. In this way, cooperatives are enterprises that put people before money and work before capital.”

Law #2: When allocated to indivisible reserves, a portion of profits is not taxed.

Italian cooperative law allows cooperatives to be exempt from paying taxes on a certain percentage of net profits if they are assigned to indivisible reserves. As a method for the Italian Treasury to obtain more taxes from cooperatives, the amount of the exemption was recently lessened. Still, the policy on assigning a portion of net profits to indivisible reserves remains valuable to the cooperative movement. Under the new law, a co-op that conducts the majority of its business with members (over 50 percent of employees in a worker co-op, over 50 percent of sales in a consumer co-op) is allowed to exempt a greater proportion of net profits from taxation than a co-op that does less than 50 percent of its business with members. The exempt portion is at least 30 percent for the former.

The philosophy behind this policy appears to be that the public purpose of a cooperative is to serve its members. Retaining profits and applying them to indivisible reserves means that they will serve a public purpose, whereas if they were given to the members, they would create private gain. Given that a co-op’s indivisible reserves must be transferred to a national cooperative fund if the co-op closes or sells, then the retained profits will always have a public purpose.

The outcome is that co-ops have a tool that permanently strengthens their balance sheet and provides them with capital for expansion.

Clusters

A topic of importance covered previously in Cooperative Grocer deserves highlighting again. Cooperatives of all affiliations benefit from the immense clustering of co-op economic activity within Emilia Romagna, where co-ops generate over 30 percent of the region’s gross domestic product.

Dollars that cooperatives have in Emilia Romagna are revolved extensively within the cooperative sector. For example, a COOP hypermarket shopping center will use eight different consortiums of cooperatives within Legacoop to carry out the following tasks:

1. purchase and operate the real estate;

2. build the shopping center (usually built by worker cooperatives);

3. finance the property;

4. manage, clean, and maintain the property;

5. provide security to the property;

6. provide the accounting service;

7. train personnel; and

8. link to Co-op Italia.

COOP does a large portion of its economic volume within the Lega family and with other co-ops.

The keys to the success of COOP in Emilia Romagna are practices based on a solidarity economy and reciprocity among cooperatives. Strengthening this base is access to solidarity capital through the creation of reserves that are indivisible by law and development funds that are mutual by design. When co-op principles, practices, and profits take place on a daily basis among thousands of cooperatives, a thriving cooperative sector comes to life. The level of cooperation in daily life in Emilia Romagna has created a synergy and presence unmatched by any other region in the world.

The results are there to see in the quality of life that emanates from cooperatives being a third of the regional economy. As a region within Italy, Emilia Romagna now has the highest income per capita (the 15th highest of all regions in Europe), the highest disposable income, the lowest income inequality, and the highest amount spent on arts and education.

Two respected voices about the regional economy of Emilia Romagna both speak and write favorably about the contribution of cooperatives. Professor Stefano Zamagni of the Cooperative Center of the University of Bologna states: “One of the major determinants of social capital is cooperatives.”

Flavio Del Bono, the finance minister of Emilia Romagna is very proud of the role cooperatives play in the region, “The presence of cooperative firms is a stabilizing element of the regional economy.”

What we see in Emilia Romagna is how a region works for the benefit of all when cooperatives are a large part of its economy. More importantly, we see how cooperation works when cooperatives cluster their economic activity and cooperators adopt solidarity practices and work together towards a shared vision.

***

David Thompson is the author of Weavers of Dream: Founder of the Modern Cooperative Movement. His Cooperative Community Fund work can be found by visiting www.community.coop.