Building a Strong Top Leadership Team

In many co-ops, the manager and board of directors function effectively as a leadership team. Along with having systems and structures in place that support and encourage healthy personal and professional relationships, a key element in each of these high-functioning teams is a general manager (GM) who has accepted responsibility for strengthening the board-GM relationship.

Through interviews with a number of managers who have healthy professional relationships with their boards, I found that they employ a surprisingly consistent set of skills, tools, and techniques for this part of their job. They each begin with a deeply held belief that democratic control, and thus an effective board of directors, matters. As servant-leaders within the cooperative, they use that belief as the foundation for their intention to strengthen their relationship with the board.

Honest and proactive communications

Communication is a critical component of all functional teams. GMs who have good relationships with their boards commit to honesty. Each manager I spoke with highlighted their inclination to make sure the board hears what Molly Langley of Sioux Falls Co-op describes as “the good, the bad, and the ugly.” In particular, these managers make the effort to ensure their board hears bad (or just hard) news directly from the GM first.

Several of the managers I spoke with echoed the “no surprises” mantra. Rochelle Prunty of River Valley Market says, “I do everything I can not to let the board be surprised by information. If I see something coming, I want to let them know it’s coming—and I want them to know I’m working on it.” Jim Ashby of Bellingham Cooperative says, “Are some directors likely to hear about this from their friends? I’d rather they hear it from me. And I never want them to be surprised or embarrassed by something in public.”

Accountability

The board delegates authority to a GM so that the GM can then effectively manage a successful co-op and make a positive impact in the community. The manager’s job is to show the board that he or she understands what the board wants, and then to be accountable to the board for how the co-op is achieving the board-determined goals. Managers use written reports as a primary tool to demonstrate accountability. Good monitoring reports—meaning reports that are accurate and include the right amount of relevant data—are a proven component of good board-manager relationships. A number of the managers I spoke with have found that the reporting templates in the CBLD Library (Cooperative Board Leadership Development Library: www.cdsconsultingcoop/cbldlibrary) help build a strong and well-informed leadership team.

In addition to reporting on policy, GMs with good board relationships use a regular (at least monthly) informational report as another opportunity to nurture that relationship. Steve Watts of Los Alamos Co-op sends the same update to his board that he sends to his management team. All managers can and should see that they are part of a leadership team, and that they have a responsibility to ensure that the team has important, relevant information that helps those leaders understand the state of their co-op—information that can help the board make smart decisions.

Supporting strategic leadership

Along with providing informational updates and policy monitoring reports that include current information, GMs with a commitment to supporting the board’s strategic leadership work also provide other information: industry and market context information, data about the co-op’s historical trends, and business plans that show how projected growth and change connect to the co-op’s Ends or mission.

At River Valley Market, Prunty’s monthly reports always include one or more charts showing historical trends for data that is particularly relevant to the board’s work. In addition, Prunty and her board have used retreats as an opportunity to make sure that the board understands management’s thinking about the future business needs and direction, and to make sure that the board and management are aligned with operational plans and the board’s role in setting direction and supporting movement in that direction.

Participating in board meetings

Managers can and should approach board meetings in a way that both strengthens the board-GM team and supports accountable empowerment. Michael Faber of Monadnock Co-op says, “I am definitely an active participant in the conversation. I will tell the board what I think is best for the co-op and why. But I also accept that the board has authority.” Rita York Hennecke of The Merc goes into board meetings with these thoughts in mind: “I’m going to be helpful. They’re my boss, but I have the most institutional knowledge.”

Managers can initiate or encourage expanded participation in at least some board conversations. Bringing other members of the management team into relevant parts of board meetings and board retreats helps the board members develop a deeper understanding of the business and helps other managers develop a deeper understanding of the board’s perspective and role. GMs can work to keep the conversation safe by regularly reminding all involved concerning who has authority for various decisions. Finance managers can help answer questions about the ongoing financial conditions and the planned budgets; human resources managers can help answer staff-related questions.

Several GMs emphasized that, while they actively participate in board conversations, they also work not to respond to every statement or question that directors may raise; they recognize that it’s often more valuable for the board’s development to have directors engage in the conversation with each other. Managing a balanced participation in the conversation is one key element of maintaining a healthy team dynamic.

Managers demonstrate a commitment to the growth of the board-GM team and of individual directors by working to listen to the opinions and questions of individual directors without taking those opinions and questions as a personal affront or as a voice of authority. By listening carefully for what a director may be expressing, the manager can then respond with his or her own professional opinion, insights, and clarifying questions. In this way, the manager demonstrates that she or he does value the contributions of individual directors and is committed to ensuring the board as a whole has the best information available in order to make the best decisions possible.

Between board meetings

Regular communication and contact go a long way toward strengthening relationships. A typical pattern for boards and managers that work well as a team is for the GM to meet with the board president at least once between board meetings. These regular check-ins offer the opportunity to think and plan together about the confluence of board and operational work, as well as to build a professional relationship between two individuals who have special servant-leadership roles within the co-op.

Prunty, whose board prefers including all officers in this monthly meeting, sometimes uses this as an opportunity to introduce new ideas or concerns; the group together can then decide the best way to bring this new information to the whole board.

Recruiting and orienting directors

Several of the managers I spoke with highlighted their role in the board recruitment process. They take great care not to exert undue influence in a way that is self-serving, because each of them begins with that commitment to democratic control. Yet they recognize that a strong board is important for the cooperative, and their active participation can help ensure the members have ballots populated with well-qualified directors. Even though the primary motive is not self-serving, these GMs understand that it’s easier to have a good relationship with the board when that board is comprised of good directors.

At Bellingham, Ashby offers this perspective: “I don’t actively recruit, but I do participate in identifying what kind of candidates we want.” Taking this notion one step further, The Merc’s Hennecke adds that she will reach out and encourage directors who might be a good board president.

Once directors are elected, the GM can immediately help usher the team through the forming stage and into the performing stage of development by participating in the orientation. (See “Building a Positive Board Performance Culture” in the CBLD Library.) Take the time to get to know new directors, and share some of the co-op’s history. Explain how the business works, how you provide information to the board, and how you want the relationship to work. This relatively small investment of time can pay big dividends.

Supporting the board

As Monadnock Co-op GM, Faber emphasizes the importance of reaching out to directors for their input and insights. Role clarity is an important ingredient of a healthy board-GM relationship, so he makes sure to remind everyone that, when asking for input, he is not asking the board to make the decision. But this is a way to demonstrate that the board and manager together are a team, and that the GM respects directors as individuals and values their insights and wisdom.

Healthy relationships are reciprocal; managers who want boards to support them also support their board. This support takes a number of common concrete forms. At well-established co-ops, managers can ensure that the board has professional administrative support—a person (or persons) who can do everything from taking minutes, to compiling and distributing meeting packets, to arranging logistics for board retreats, and more. Ashby notes that Bellingham has approximately one full-time equivalent position devoted to board support.

Managers can encourage the board to invest in training and education. A responsible board might rightfully hesitate to use co-op resources; a responsive manager can help the board see that spending money in this way benefits not only the current directors, but also the entire cooperative, now and into the future. Managers who encourage this sort of ongoing training find that they themselves benefit from a professionalized board. Directors who aren’t expected to scramble to do all the administrative work required for the board to function have the capacity to contribute to the team’s strategic leadership work.

Appreciation is another area ripe for reciprocity. Good managers know that it’s important to appreciate the efforts of the co-op board as much as it is to appreciate the efforts of employees. Faber brings to life his intention to create a culture of appreciation by looking for opportunities to say thank you to the board for their ongoing efforts, as well as to individual directors for a helpful insight or a thought-provoking question. Along with thanking the board, managers who nurture this relationship also take great care to avoid saying anything negative about the board and to find opportunities to appreciate the board when speaking to staff, co-op members, or the public.

Summary

In physics class long ago, I learned that systems tend toward entropy unless someone or something puts energy into the system. Boards need someone to put energy into helping the board function well, and the managers I spoke with all assert that they understand this as part of their job. Managers with a productive relationship with their board take responsibility not for managing the board, but for managing the relationship. They ask themselves: “What kind of relationship do I want?” They then work to manage for what they want. As Ashby notes, “It’s worth the work.”

The Four Pillars of Cooperative Governance model helps us see that everyone in the cooperative has some role in the co-op’s governance. Responsible managers understand their governance role. They approach this role, and specifically their relationship with their boards, systematically by attending to each of the four pillars: teaming, accountable empowerment, strategic leadership, and democracy. (See Cooperative Grocer #170 and #171, Jan.-Feb. 2014 and March-April 2014.)

Managers should manage this critical relationship conscientiously. Our cooperatives depend on the ability of elected lay boards to hire professional managers who can make things happen and on the ability of those managers to understand the will and values of the members as expressed through the elected board. Cooperatives are simultaneously associations and enterprises. Hennecke describes a fundamental understanding she brings to her role: a strong board-GM team becomes a foundation that can then support a thriving association and a successful enterprise.

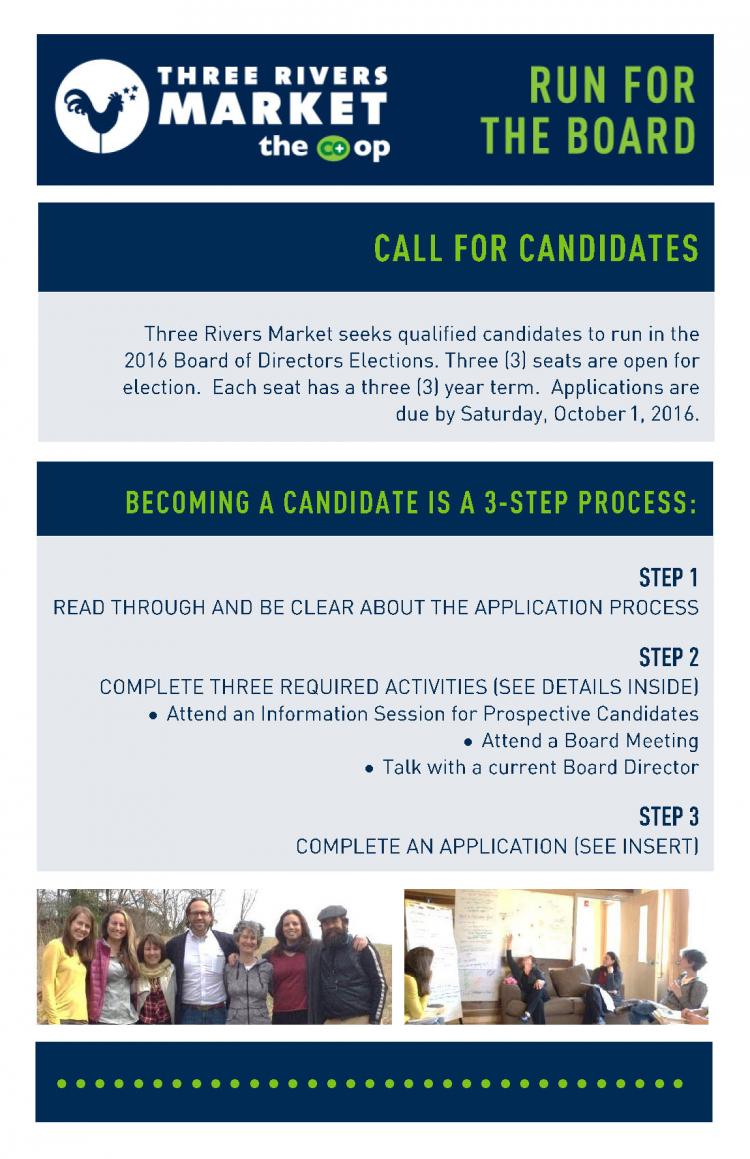

Image: Clear instructions about the board job, from Three Rivers Market in Knoxville, TN