Catching the Wave

Ten years ago, something shifted. New food co-ops, most stemming from the 1970s, had been rare since the 1980s recession, and many—probably at least two-thirds—of these new wave co-ops had closed or were folded into a surviving co-op. Slowly at first, beginning more than a decade ago, a third wave of retail food co-ops began to build and soon became a force.

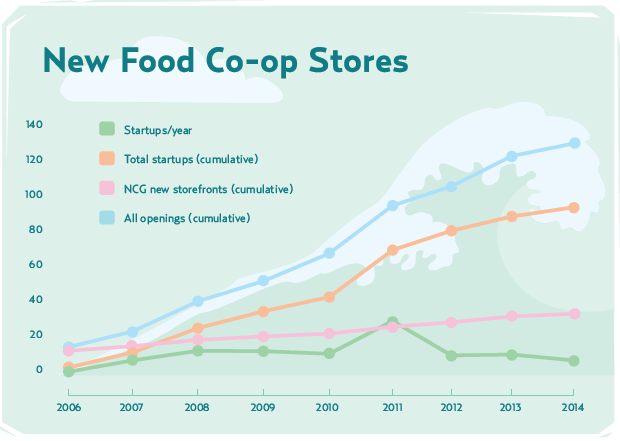

Food Co-op 500, now the nonprofit Food Co-op Initiative, began tracking these stores in 2006 and has recorded 95 openings over eight years. Allowing for a few that opened before we began tracking and those that have closed, there has been a net gain of about 70 co-ops.

Since 2003, National Co+op Grocers (NCG) member co-ops have opened an additional 31 storefronts. According to the Cooperative Grocer Network directory, we now have 385 retail co-op stores. Combining NCG members’ additional storefronts and the startups, the net total represents a 36 percent increase in the number of retail food co-op stores in the U.S. over the past 12 years.

Food Co-op Initiative conducts an annual survey of all the startup co-ops to track their status and growth. For the calendar year of 2013, we got responses from about two-thirds of the co-ops. We used that data to estimate the following impacts for the recent wave of food co-op startups:

- 90,000 new member-owners

- 1,011 full-time equivalent jobs

- $154 million in combined annual revenue

Data was not available for the NCG stores, but it is safe to assume that its 31 co-ops were much larger on average and hence would more than double the figures from startup co-ops.

Some 30 new co-ops are known to have closed, and while we regret the loss of any co-op, we have an enviable success rate of nearly 74 percent—the grocery sector as a whole has one of the highest new-store-failure rates. Co-ops that failed remained open an average of two years, with one lasting less than a year and a few hanging on for four to five years. Most of these co-ops were very small, with sales of under $1 million/year. Many were under-capitalized or had too little sales revenue to remain viable. A few larger startups also closed, often due to miscalculations in their original business plans.

About 70 percent of the new co-ops have sales of $1 million or less. These stores are especially vulnerable, since they are not eligible for NCG membership and are reliant on their own, limited resources. The top 30 percent have average sales of $3.8 million. As support and resources for new co-op development have grown, we are seeing a trend towards more professional business planning and larger store sizes. While larger stores have a better track record, the costs to open them have been increasing dramatically. A few years ago, a 10,000-square-foot facility (gross) might have had a startup budget of $250/square foot or $2.5 million. That represents a lot of member equity and loans, but as renovation and equipment costs have soared, that same store now might need a budget of $325/square foot ($3.25 million) or more.

These budgets are leading startup boards to seek more equity, often through preferred shares, to offset otherwise unsupportable debt loads. Another impact is an increase in the projected sales/square foot required for viable pro-forma budgets. Whereas $400/square foot used to be a benchmark, $600 may be needed today. This creates additional pressure for organizers to scale back on store size in order to maintain realistic capital requirements—yet hoping to meet revenue projections that may have been based on more square footage.

The reliance on owner capital is a significant limitation for almost all new food co-ops. There are practical limits to how much money the community can invest and reluctance from conventional lenders to back new businesses. The idea of starting small and growing has great appeal, but rarely is it successful. For these reasons, it is likely that many grassroots startups currently in development will plan stores that are large enough to be viable but may not be as large as the market demand could support.

Creativity has always been a hallmark of food co-ops, and we are starting to see quite a few innovative capital strategies. More startups are working with developers who can carry some of the startup expenses in return for future lease revenue. Crowdfunding has been effective for raising modest amounts of development income for some co-ops, spreading awareness in the community as a fringe benefit. However, crowdfunding efforts rarely net more than $10,000 to $20,000—not much in the big picture, but important in that it can be available before the co-ops’ major capital campaigns have begun. Direct Public Offerings (DPO’s) have been getting a lot of attention as an alternative to the traditional securities exemptions most co-ops have used in the past for loan campaigns. New, high-risk loan funds are being planned by mission-oriented lenders that may help leverage additional long-term loans. And thanks to the stellar reputation of our established co-ops, economic development funds are reaching more co-ops.

How long will this third wave of retail food co-op development last? Previous waves have peaked after about 20 years and then begun a slow decline in numbers as stores close or merge. But successful new co-ops continue to grow and prosper, and total sales volume may peak decades later. Are we halfway through our current “up” cycle? If so, we can expect about 10 more years of strong growth for co-op storefronts. We may be able to extend our wave by providing high levels of support and encouragement to communities that are exploring co-op options.

Innovative ideas may open new paths to easier cooperative startup. We may even see a greater understanding and interest in co-ops as efforts proceed to bring cooperation to the forefront of economic debate. However, there are many challenges, and most such issues are only becoming more problematic. Startup costs, management shortages, increasingly sophisticated competition, potential shortages of organic foods—these are issues that will affect the entire food co-op sector. Now is the time for us to act, strengthening our existing stores and supporting new co-ops that will add to our collective strength.

Co-ops are not the only businesses facing unprecedented change, but unlike most we have a history of innovation, resilience, and the support of the communities we serve and nurture. Let’s get on our boards and ride the wave before it breaks.