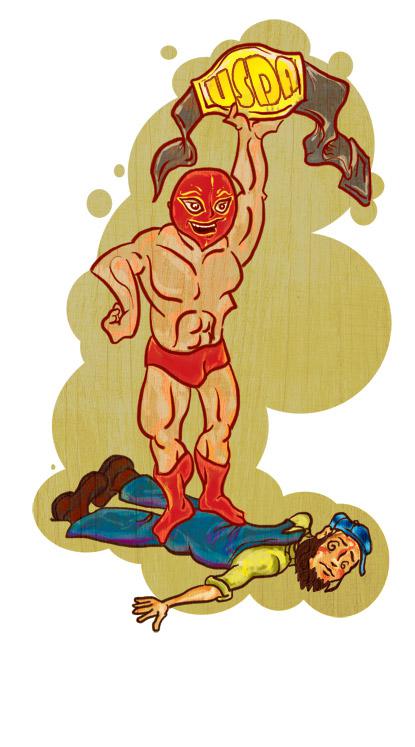

USDA Power Grab on Organics

The USDA’s National Organic Program (NOP) stands accused of a power grab after changing a fundamental decision-making process impacting organic food and agriculture. Miles McEvoy, the NOP’s deputy administrator, in late 2013 announced a dramatic change in the process for approving the continued use of certain non-organic and -synthetic materials in organics.

Non-organic and synthetic materials are banned from use in organics, but limited exceptions are allowed and itemized in federal organic regulations known as the “National List.” Every five years, each item approved for use receives a technical reevaluation to determine whether continued use of the material threatens human health or the environment and whether an organic-produced alternative is available. This is known as the sunset process—if a material is not reapproved, its use in organic production ends.

“The use of synthetic substances in organic production and processing is an exception, not an entitlement,” notes Jim Riddle, a respected former chair of the National Organic Standards Board (NOSB). The NOSB was created by Congress in the Organic Foods Production Act to advise the USDA secretary on policies impacting the organic industry and to specifically oversee and carefully review for approval any synthetic and non-organic material or ingredient used in organic farming and food production.

The NOSB was designed to be composed of various organic stakeholders with a minority of its members representing corporate agribusiness; other members come from the farm community and environmental, scientific, and public interest organizations. And in an attempt to push the oversight of the industry towards consensus, the federal regulations require a two-thirds majority for “decisive” votes. This process is designed to ensure that wide agreement supports the use of the any material in organics.

Changing the rules

Federal bureaucrats, with no public discussion, have arbitrarily changed the rules of the game. Instead of requiring a sunset material to win a two-thirds vote allowing its continued use in organics, the process would now require a two-thirds vote to remove a material from use. The change was justified as a way to “streamline” the sunset process.

“The USDA has turned the entire sunset process on its head,” says Barry Flamm, another former NOSB chair. “Instead of needing a super-majority to continue using a synthetic in organics, the NOP has, without the legally required consultation with the NOSB, published an edict requiring a two-thirds vote to instead remove a material.”

Many of the materials on the National List are not controversial. For example, hydrogen peroxide; livestock vaccines; and Vitamins B, C, and E are allowed synthetics. Dairy cultures and yeast also are allowed nonsynthetics. Celery powder and pectin are further examples of agricultural materials unavailable in organic form that are on the National List of approved exceptions for use in organic production.

However, a number of materials have caused heated debate at recent NOSB meetings. Carrageenan, narrowly reapproved for use in 2012, is a synthetic food additive that public-interest organizations have been extremely critical of, based on published research indicating its inflammatory impact on the digestive system.

Large food manufacturers and the powerful industry lobbyist, Organic Trade Association (OTA), petition the NOSB for the addition of more and more gimmicky nutraceuticals for use in organic foods. For example, DHA (from genetically mutated algae) was an intensely contested material that the corporate-dominated NOSB narrowly approved in 2011.

Following the DHA fight, The Cornucopia Institute began a careful review of the materials approval process and published The Organic Watergate. Cornucopia documented a corrupt relationship between agribusinesses that had invested in organics and USDA officials. The report exposed the existence of biased technical reviews considered by the NOSB and the stacking of the board with industry executives in seats that Congress reserved for farmers and scientists: independent stakeholders.

“We focused sunlight on the fraud and deception in the process,” observes Will Fantle, Cornucopia’s codirector. “The result was a turnaround at the NOSB, which has more recently acted judiciously in preventing some synthetics from entering the organic production stream.”

As an example, since the release of The Organic Watergate, the NOSB has denied petitions for several synthetic preservatives proposed for use in infant formula, rejected unnecessary additives such as sugar beet fiber (likely made from GMOs), and voted to discontinue the use of tetracycline, an antibiotic used to control fireblight on apples and pears—all because of concerns regarding human health and environmental impact.

“The OTA and its members (WhiteWave, Kellogg, Smucker, Safeway, etc.) have seemingly lost control over the NOSB process,” adds Fantle.

The tipping point that pushed the USDA into changing the materials-approval process may very well have been the NOSB’s failure last spring to reapprove continued use of the antibiotic tetracycline in organic orchards, a material which was due to sunset.

Corporate representatives were stunned by the outcome. They have, however, been very supportive of the recent change in decision-making by the NOP. Melody Meyer, the newly elected board chair of the OTA and the vice president of policy and industry relations for United Natural Foods, Inc., wrote a blog post entitled “Stop the Lies and Get Behind Your National Organic Program.” In it she charged that concerns raised by public-interest groups over the process change were “bogus.” Meyer instead applauded the “gusto and vigor the [NOP] delivers to our growing industry.”

Meyer’s comments followed the release of a joint statement from several Cornucopia allies, Beyond Pesticides, Consumers Union, Food and Water Watch, and Center for Food Safety, challenging the reversal in organic governance.

Jay Feldman, the executive director of Beyond Pesticides and a current NOSB member, says any change to the decision-making process “should have been subject to public review.” He expresses a concern that instead of “driving the board to consensus,” as Congress intended on materials allowed for use in organics, members of the organic community may “start to view the organic label as undermined.”

The OTA’s perspective proved too much for longtime member and former NOSB Chair Jim Riddle. In an open letter, Riddle announced he could not, in good conscience, renew his membership. Riddle wrote that, “Ms. Meyer displayed an alarming lack of understanding of the Organic Foods Production Act and the National Organic Program Final Rule, as well as disrespect for public interest groups who have been part of the organic movement from the beginning.”

USDA management has been ignoring NOSB decisions on other matters as well. One recent example again involves carrageenan. When the board granted its relisting as an allowed substance, it stipulated that carrageenan could not be used in infant formula. Infant digestive systems, as most people know, cannot tolerate solids in the first few months of life. Carrageenan acts as a coagulator, which has led to its prohibition in infant formula by the European Union. When the NOP issued formal rules for its use, they ignored the NOSB’s restriction.

Cornucopia and other organizations concerned with organic integrity are examining their options. “We may very well end up in a court battle over this latest abuse,” says Fantle.

“The stakeholders who truly care about the integrity of the organic label and the principles it was founded upon are not going away,” affirms Kevin Engelbert, the nation’s first certified-organic dairy farmer, a Cornucopia board member, and a former NOSB member himself.