Small Co-op Realizes Larger Vision

Eight years ago, the Lexington Co-op (Buffalo, N.Y.) was a hole in the wall doing $800,000 out of 1,200 square feet of well-worn retail space. Our equipment was ready to be replaced, our floor was beginning to wear out, and our ideas of what we could be were much larger than our balance sheet could support.

This article is the story of how we turned these lemons into lemonade. It is intended to be useful to small co-ops dreaming of expanding their offerings and anyone else working on an expansion project.

Getting our house in order

In 1997, the Lexington sustained $50,000 in losses. When this was added to eight years of flat sales growth and negative profitability, our net worth was threatening to go into the red. Cash flow was an everyday concern. The finance committee recommended closing the store.

The same day that recommendation was made, a few of us walked through a 7,000-square-foot space on the main retail street in the neighborhood. It was perfect. We loved it. We knew we couldn’t afford it. But instead of closing, the board and staff set to work at getting our house in order so we could take the next opportunity that came our way.

The first thing we worked on was sales. We stocked the shelves to bursting with natural foods and homegrown produce. We made sure the store was faced, clean, and ready when the first customer arrived at 9:00 a.m.

We began performing store opening walkthroughs with staff to build a collective vision for how the store should look and build accountability at all levels of staff. We created checklists to ensure that staff had a clear idea of what was expected of them every day, and co-op staff began wearing nametags and aprons. We expanded staff orientation to include basic customer service training.

The great thing about most of these changes is that they cost us nothing. We had had a great staff at the co-op for years. They just needed to be given clear direction in order to be successful.

Our customers responded, and sales grew steadily at 10 percent for the first two years, then jumped to 30 percent growth for the next two.

After learning to keep more customers happy, we started getting our offices in order. We overhauled our bookkeeping system, made the transition to policy governance, made sweeping changes to our bylaws, and started building a management team—all with the goal of clarifying roles and building accountability throughout the organization. This work paid off, and within two years, we had made $80,000 in profit, bringing our balance sheet back from the dead.

Next, we started crafting a vision of what we wanted. We held a strategic planning session with member-owners, board, and staff. We had discussions at every annual meeting and held 12 member forums over three years with topics such as, “How do you see the co-op in five years?” and, “Should the co-op have a deli?” Often, there would only be a handful of people in attendance. But this work with our member-owners did two things—it legitimized our vision (this would be critical as the process dragged on), and it got us in the habit of talking to member-owners, so that later, when there were controversies with the project, we knew how to communicate with them.

We emerged from this process with a vision of a co-op that was in the neighborhood, accessible to pedestrians and cars, with roughly 5,000 square feet of retail space, wider aisles, and more products. Pretty simple—but it got us through.

Once we had a vision that excited our staff, board, and membership, we started working in earnest on the project. It had been four years since the finance committee had threatened our closing, and we were ready. We ramped up our involvement with Bill Gessner of Cooperative Development Services, who met with us weekly by phone to guide us through our now-three-pronged approach: (1) building a management team that could run our much larger store (2) finding and securing a site, and (3) obtaining financing. All three facets were challenging.

Project success elements

I firmly believe that our success with the rest of the project amounted to keeping our house in order, getting lucky, listening to our consultants, leaning on our peers, and being persistent.

*We took care of our customers*—We never lost track of the belief that our most important job was to give our member-owners an amazing grocery store every day. This kept them supportive through the eight years of talk that led to our new store.

*We got lucky*—Our favorite site became available at the perfect time.

The National Cooperative Bank (NCB) became re-engaged with financing food co-ops about a month before our offer was accepted on our preferred site. NCB provided $1.6 million in construction and equipment financing.

Northcountry Cooperative Development Fund (NCDF) agreed to extend their trade area to finance our project in part because they had made a loan to a housing co-op in Buffalo through North American Students of Cooperation, which was in their trade area.

Every time we hired for a key position, the right person walked in the door; often, they were the only qualified candidate. It amazes me that we were able to hire such a strong management team out of our dinky little store.

*We followed the instructions of our consultants*—If Bill Gessner was wrong about something during the course of this project, I would be hard pressed to remember what it was. Bill and the entire Cooperative Development Services group are an amazing development team to have in place.

One of the best moves we made was to hire an experienced owners’ representative/project manager to work with the architect and contractor. Our net change orders were less than 5 percent of construction costs, and construction was completed on time, thanks mostly to Jad Cordes, president of Integrated Realty and Development, and his skill in managing our general contractor.

*We leaned on our cooperative contacts*—We networked every chance we got—selling the project to anyone who would listen.

At the 2003 CCMA conference (see p. 18), I met two people that would play a critical role in the success of this project: Diana Sieger from Outpost, who provided key merchandising help during those last few frantic months; and Margaret Lund from NCDF, who provided financing at a critical juncture. I went to that CCMA conference desperate to find $750,000 so wecould start construction. I didn’t come home with quite that much, but the contacts I made there proved invaluable down the road.

When the National Cooperative Bank required that we secure deposits from two other co-ops to leverage their financing, our sister co-ops in Brattleboro and Flatbush stepped up and pledged the funds, mainly on the strength of relationships developed over years of participation in our regional and national associations.

*We kept pushing*—We raised $560,000 in member loans—$260,000 prior to securing a site—on the strength of the vision we had built. Our average loan size was $3,000. The keys to our success? Overwhelmingly supportive and generous member-owners, and we just kept asking until we reached our goal. The success of the first round of the loan drive was key—it gave our member-owners confidence in our chances for success and gave us the credibility we needed with the sellers of our preferred site.

As we were putting the financing package together, I was on the phone to the lenders every day—setting up meetings, making sure they did what they said they would, and just keeping us in their view.

At every stage of the project, being relentless about putting our project on other people’s agenda was my most important task. Cat herders have nothing on co-op project managers.

We also kept pushing ourselves to be better. We had to learn how to manage a team of managers, how to manage public relations when the timeline dragged on, how to put together a financing package—pretty much everything about managing the project, we had to learn.

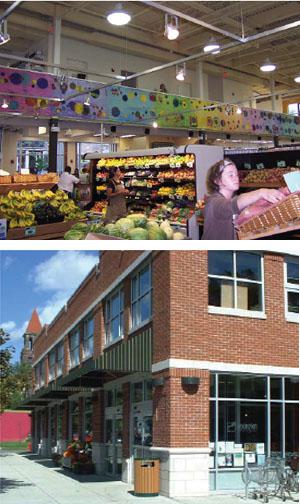

We moved into our new home on July 27, 2005. We have 4,500 square feet of retail space, and it already seems too small! Our sales are already at $1,000 per square foot and are 10 percent above projections. We have lots of work to do—much of our décor and signage systems were not figured out before the move, and we have the usual problems from making a leap like this.

Our member-owners and customers love it. Thank you to everyone in the co-operative community who helped us with this project!

***

Tim Bartlett is general manager at Lexington Co-op in Buffalo, New York ([email protected]).